The cost of living in America

I’ve been trying to read more serious books recently. One that I picked up, on J.W. Mason’s recommendation, is “The Cost of Living in America: A Political History of Economic Statistics, 1880-2000” by Thomas A. Stapleford.

The book chronicles the history of price indexes, primarily the consumer price index (CPI/CPI-U), over more than a century. For those who don’t know, CPI is one of the most important economic statistics, and one that, along with the unemployment rate and GDP, has permeated into public consciousness. It is widely used. It tries to measure “inflation” (how fast prices are rising), but it is not solely a price index. It is also used to make income/wage adjustments: it powers the conversion between nominal and real wages, it factors into the social security cost of living adjustments (COLA), it is used to adjust federal tax brackets, and, perhaps most controversially, it tries to capture whether people and households are “better off”, economically, than they were before. The idea is that if your wages or household income are rising faster than your prices (as measured by CPI), you should be able to afford a higher standard of living than before.

The book is, as the subtitle explains, a work of political history. My only complaint is that I wish it had touched more on the economic and mathematical issues associated with CPI itself. The basic problem is described in this passage from a report from the American Statistical Association (ASA) in 1943 (pp. 199):

The phrase “cost of living” is ambiguous…In every-day speech families are apt to think of their cost of living as the total amount they spend for consumer goods and services. Several different factors may cause such expenditures to change. Thus, they may change because the unit prices of goods and services rise or fall. Again, they may change because families are forced by circumstances beyond their control to alter their manner of living, as when the exigencies of war make some goods unavailable. Yet again, they may change because families have experienced an increase in income and can afford to buy more goods or better goods. … As used in technical statistical parlance, the term “cost of living” has applied only to the first of the factors which determine family expenditures, that is, to unit prices.

Things have changed somewhat since this report. The BLS has replaced the “constant goods” version of CPI, which used fixed weights, with a “constant utility” version of CPI, which allows weights to change periodically (annually for CPI-U, monthly for chained CPI). The constant goods version of CPI only captures changes associated with unit prices of goods. The constant utility version, by contrast, does account for changes in “weights” as well. But the key issue remains: does CPI truly measure cost of living? And if not, why not?

I think it’s useful to walk through a few toy examples:

Example 1

Let’s suppose there’s only one household in the U.S., represented by Norm, the head of household. (This avoids difficulties associated with the price index, which is an average, being unrepresentative of a particular person, like you.)

Norm is the sole wage-earner. He makes $100,000 and saves basically nothing. (Like most Americans who aren’t in the top 10%.) Let’s simplify and suppose there are two categories of expenditures: essentials and discretionary. See table below. Norm’s household’s costs for essentials go up by 10% over a year. His rent increases, his electricity bill rises, and groceries get more expensive. To be more precise, the unit costs of this “bucket” goes up by 10%, and, because these are all essentials, his household can’t consume less of them to save money — his demand is inelastic.

Suppose also that the unit costs for discretionary items stay flat. (These might be things like new electronics or flights to a beach destination or a weekend trip to a National Park.)

(As an aside: Unit costs might be flat because, even if discretionary items are nominally more expensive, their quality is also higher, and CPI adjusts for quality (the “hedonic adjustment”). A 5% “better” TV that costs 5% more is treated as a 0% price increase for TVs.)

Finally, suppose Norm gets a 5% raise at work. See table below.

| Time point | Essentials spending | Discretionary spending | Salary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 2015 | $50,000 | $50,000 | $100,000 |

| Jan 2016 | $55,000 | $50,000 | $105,000 |

Because Norm’s essential costs have risen, his entire salary increase gets spent on those additional costs, leaving him nothing extra for discretionary consumption.

In the CPI calculation, the “weights” are the fraction of expenditures in each bucket at the beginning of the period. So, essentials = 0.5, and discretionary = 0.5. The price changes are 10% and 0%, respectively. So the price index increases by 0.5 × 0.1 + 0.5 × 0.0 = 5% — exactly the same as Norm’s salary. CPI would say Norm is no better or worse off than before: his “real” salary has not changed.

In some sense, this is true. Norm’s income is exactly keeping pace with his additional expenses. And, in fact, if you extend the calculation forward, stepping 1 year at a time, you find that, each year, Norm’s real income is unchanged (provided that we “chain” the calculation each year by adjusting the weights, which is usually the case.)

What is disturbing, though, is that the cost of the stuff Norm needs is rising faster than this income. It’s arguably worse to make $X more and to have to spend $X more, because if you lose your job, your salary drops to zero but your essential expenditures do not. (This is a bit like the uneasy feeling people get when they make more money but also have a larger mortgage payment, kids to support, etc.)

The basic problem is that the CPI assumes your “cost of living” is “the cost of the goods and services you spend your money on”. If your entertainment budget is half your spending, it counts towards 50% of your CPI calculation. But intuitively it seems like the cost of living should be weighted more (if not entirely) towards essentials than non-essentials.

In Stapleford’s book, he talks about a convention of labor statisticians in 1934, where “a substantial majority” of the attendees “favored the creation of a new “health and decency” budget to provide a substitute measure of the “cost of living””. “Health and decency”, I think, captures something like the intuition above. There is the rate at which essentials go up. And there is the rate at which everything else goes up. We should at least try to report on the former, and give it greater consideration than the latter.

The BLS studied this question in a simplistic way, and found that prices of essential categories of consumption like food, housing, and medical care have increased only slightly faster than the CPI (roughly, only 6% over 22 years, between 1982 and 2014). More recently, Mike Konzcal showed that since the pandemic, “core essentials” (groceries and shelter) have increased at a faster rate than overall prices (by 8%, although he looked at PCE instead of CPI).

Introducing a distinction between essentials and discretionary spending is along the lines of what Amartya Sen’s “capabilities approach” to welfare suggests. But, as Stapleford writes, these alternative approaches to CPI are not without peril (pp. 338-340)

Sen discards both self-reported well-being and “opulence” (the quantity and quality of possessions) as inadequate bases for assessing a standard of living. The former can be too readily divorced from material conditions by “social conditioning,” while the latter (goods themselves) provide “no more than means to other ends,” and it is the “other ends” that truly define a standard of living. The ultimate solution is to consider these ends, which Sen describes as “functionings” (the realization of particlar states or operations) and “capabilities” (the actual, not merely formal, freedom to realize a functioning if so desired.) Thus, to take an example, the state of being well-nourished is a functioning; the capability of being well-nourished implies that one has the opportunity and resources to realize that state.

…

It should be obvious that capabilities approach to cost-of-living indexes raises innumerable operational problems (how can one assess social capabilities?) and normative issues. Creating a capabilities-based cost-of-living index for indexation for federal programs would require us to identify a set of capabilities which we desire to maintain over time and to then find some means of assessing those capabilities in two different situations. Neither of these would be easy tasks.

Let’s suppose we try to identify the cost of a capability like “being well-nourished”. The food bucket in CPI includes making a meal at home, drinking soda, ordering pizza delivery through DoorDash, and eating at a Michelin star restaurant. Which of these should factor into the cost of the “well-nourished” capability? Konczal, for example, assumes “food at home” is essential and “food away from home” is not, but I certainly spend some of my grocery budget on non-essentials.

The same goes for housing. I was somewhat surprised to learn that housing expenditures are roughly “homethetic”: the share of income spent on housing is roughly constant by income bracket. Richer people buy more expensive houses and rent more expensive apartments than they need for mere sustenance or “health and decency”, or to have the capability of being sheltered.

We could spend a lot more time discussing just this example! But let’s move on to example 2, in which we consider a price index with more than just one household.

Example 2

Let’s add another household to this calculation: Rich. As his name implies, he makes a lot more than Norm, and, more importantly, his expenditures are far more tilted towards the discretionary bucket.

| Time point | Essentials spending | Discretionary spending | Savings | Salary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 2015 | $100000 | $200000 | $100000 | $300000 |

| Jan 2016 | $110000 | $200000 | $105000 | $315000 |

What happens in this case? The consumption weights in the CPI calculation are an average of Norm and Rich’s expenditures. Norm spends more, so he also counts more. Total expenditures in Jan 2015 are $100000 (Norm) + $300000 (Rich) = $400000. Of this, $250000 is discretionary, giving it a weight of 62.5% — higher than the value for Norm alone.

Remarkably, using this weight would show that Norm’s real income is increasing, not staying flat! The CPI is 0.375 × 0.1 + 0.625 × 0.0 = 0.0375. CPI has risen by 3.75%, Norm’s income has risen by 5%, so Norm should be 1.25% ahead. But he isn’t.

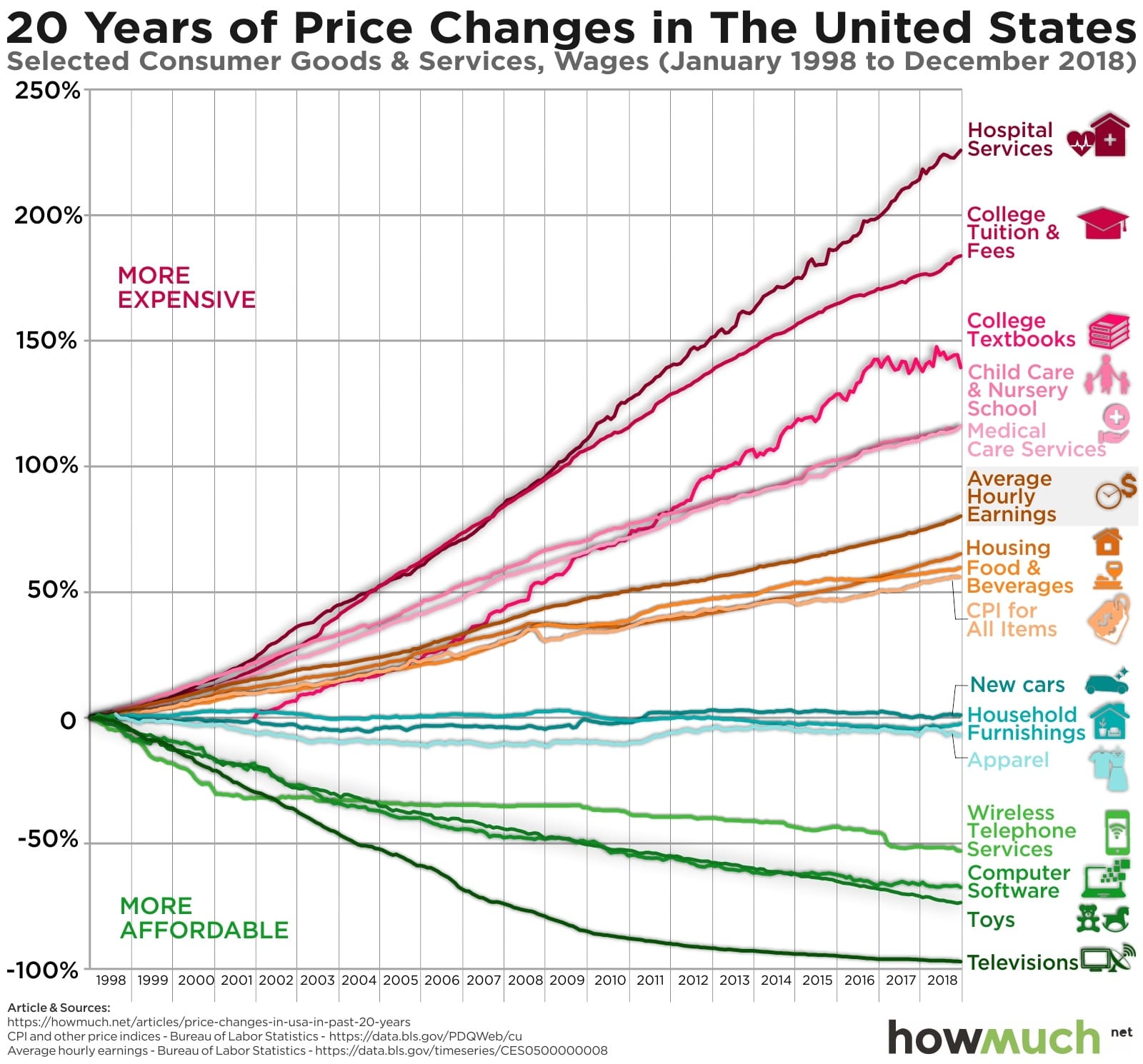

Aggregate measures like CPI have a strange “nonlocal” property where the consumption patterns of other people affect how “well off” you are, even if they don’t affect your prices directly. To the extent that people’s consumption weights are highly heterogeneous, some people will be worse off, or better off, than the average person. Those who spend more on slowly inflating (or deflating) categories will see their own personal price index rise more slowly than the CPI. Conversely, those who spend more on categories experiencing sharp increases will fall further behind than what CPI measures. You can get a sense of which categories are which by looking at this (infamous) chart

(Note: many of the price declines, particularly the extreme ones like televisions, are heavily related to the quality/hedonic adjustment discussed above. Clearly, the nominal price of televisions has not fallen by ~95%.)

A further problem that you might have noticed is that, when it comes to calculating the “weights”, wealthier households like Rich’s matter a lot more than normal households like Norm’s.

Stapleford writes (pp. 333),

Wealthier households spend more money; hence, if the national index is calculated using aggregate data (as is typically the case), the purchases of wealthy households will carry greater weight (a formulation known as a “plutocratic” index). By contrast, one could imagine a national index that is an average of each household’s individual cost-of-living index. In this version (a “democratic” index), the far more numerate lower and middle-income households would have a greater effect on the overall result. Because the use of aggregate expenditure data makes it much easier to compute a plutocratic index, all major consumer price indexes follow this form. Moreover, this is the proper basis for deflating aggregate expenditures in calculations such as the national accounts. Yet it will be less reflective of the experiences of lower-income households, a pattern that would be even worse if…the new, high-priced goods typically purchased by wealthier families are introduced into the index more rapidly.

Closing

It is remarkable to me that even relatively simple examples — with just one or two households and one or two buckets of consumption — show deep conceptual problems with consumer price indexes, particularly as used for wage adjustments. And I haven’t even delved into the boatload of other issues with these indexes: substitution effects, hedonic/quality adjustments, geographic heterogeneity, treatment of new goods, owner’s equivalent rent, omission of some categories (like mortgage interest), and so on. (Some of these are covered in a nice post by Steve Waldman at interfluidity.)

What I hope you take away from this essay is that CPI is a rough measure of how fast prices are rising, but it is not really a measure of cost of living, and it is very dangerous to use it as a wage deflator to say that the “average” household is better off (or, even worse, that your household is better off). Real income might rise but your household might be in a more perilous situation, like Norm’s.

In short: CPI doesn’t distinguish between what is needed for a decent life and what people actually consume. Neither does it distinguish between what you need for a decent life and what someone else does.